With 800+ products, there’s a lot to discover. Here, you’ll be able to go down any rabbit hole you choose, from staff recommendations to seasonal selections and everything in between. Discover something new from the world of wine, beer, and spirits.

Wine lover, find our seasonal selections here.

Non-Alc Wine

Non-Alc wine has come a long way over the years and one our favourites is from German-producer Leitz; with a style for everyone, try one of these delicious alternatives to your usual bottle of vino.

Local wine is always a great choice.

Benjamin Bridge

Explore the entire collection of products from local-favourites Benjamin Bridge, located in the heart of the Gaspereau Valley.

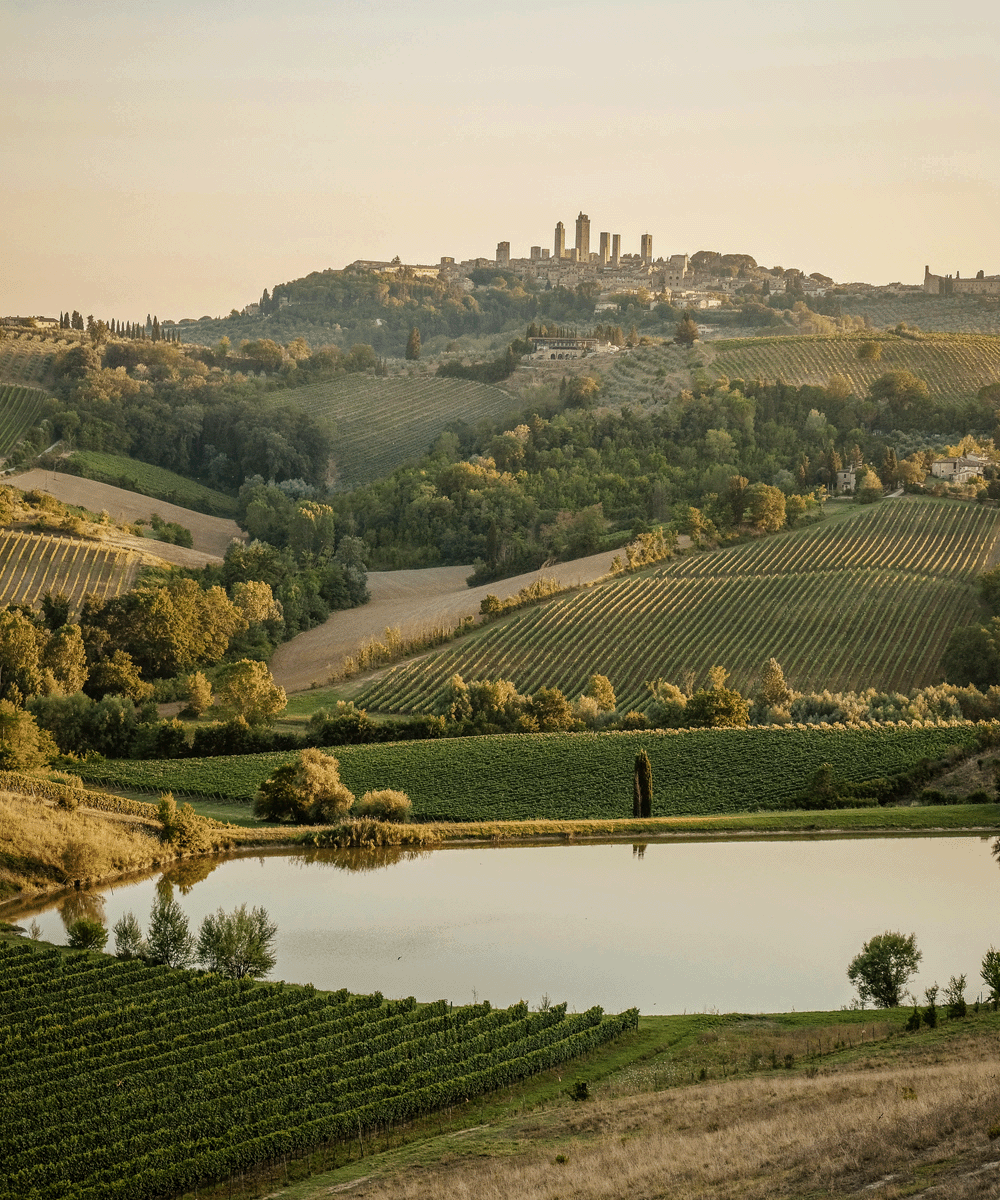

Vino Italiano

Between the rolling hills of Tuscany, the foggy valleys of Piedmont, and beautiful, sunny Veneto; there’s so much to uncover in Italy.

Your Best Buys

A wine for every budget? We have that. Here are some of our recommendations that make the most out of what you want to spend.

Curated, spirit-ed recommendations.

Long Drinks

Generally lower-abv but still jam packed with flavour. Take your favourite Gin, Whisky, or Tequila and let it shine in a long drink.

NOA Non-Alc

Our newest non-alcoholic producer, making a variety of spirits and pre-made cocktails that seemingly maintain all of the complexity and flavour you'd expect from these beverages.

Italian Amaro

Enjoyed before a meal, after a meal, and in your favourite cocktails, this herbal liqueur is the perfect addition to any home bar.

Single Malt Scotch

One of our most popular categories by a long shot. Collectors, casual drinkers, and probably your dad, all enjoy a dram of the good stuff.

Beer me some fresh selections.

Dark Beer for Fall

Nothing says cozy like your new favourite dark beer. Browse all of our seasonal selections perfect for this time of year.

Low-Alc Options

Looking to dial it back this January? Here are some low-alc brews that'll fit perfectly into whatever you have planned this month.

Local brews that deserve your attention.

Tatamagouche Brewing Spotlight

From the little town of Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia, these North Shore giants produce a killer lineup of traditional and modern styles.

Propeller Brewing Company

With locations peppered throughout the city, Propeller has been a staple and was one of the first breweries in the city dating back to 1997.